Rupi Kaur Believes Style and Stanzas Are One and the Same

Poetry, much like fashion, has always had its set of rules. In fashion, there are the expectations of how a woman "should" look to be deemed respectable. And in writing poetry, there is the added pressure of adhering to traditional forms for your work to be deemed "art." The rules of style and stanzas are something that famous Punjabi poet Rupi Kaur understands but does not follow. Her entire career flies in the face of what constitutes a "traditional" writer in every way. On the surface level, she's beyond the typical mold of what you'd expect a poet to look like—she's an immigrant woman of color who's regularly donning brightly hued gowns that are often adorned with sequins. Her mere existence inside the literary world is disruptive in an industry that's long upheld the idea that the world's most well-regarded poets happened to only be white men. But on a deeper level, you can feel how she challenges the very notion of what poetry is through her work.

Kaur first rose to prominence when she began posting her short-form poetry on Instagram. Her followers inspired her to self-publish her first book, Milk and Honey, which became a number one New York Times best seller list and landed her a publishing deal to release her subsequent collections (The Sun and Her Flowers and Home Body). Her rapid ascension into the spotlight was met with a fair share of side-eyes and critiques of her signature short poems. But in an industry steeped in traditionalism, Kaur reminds us there's no single way to write—just like there's no absolute definition of what constitutes great poetry, great style, or even what our personal "greatest" self is. We exist in a series of contradictions that can't always be summed up in 10 words, but that doesn't stop Kaur from trying.

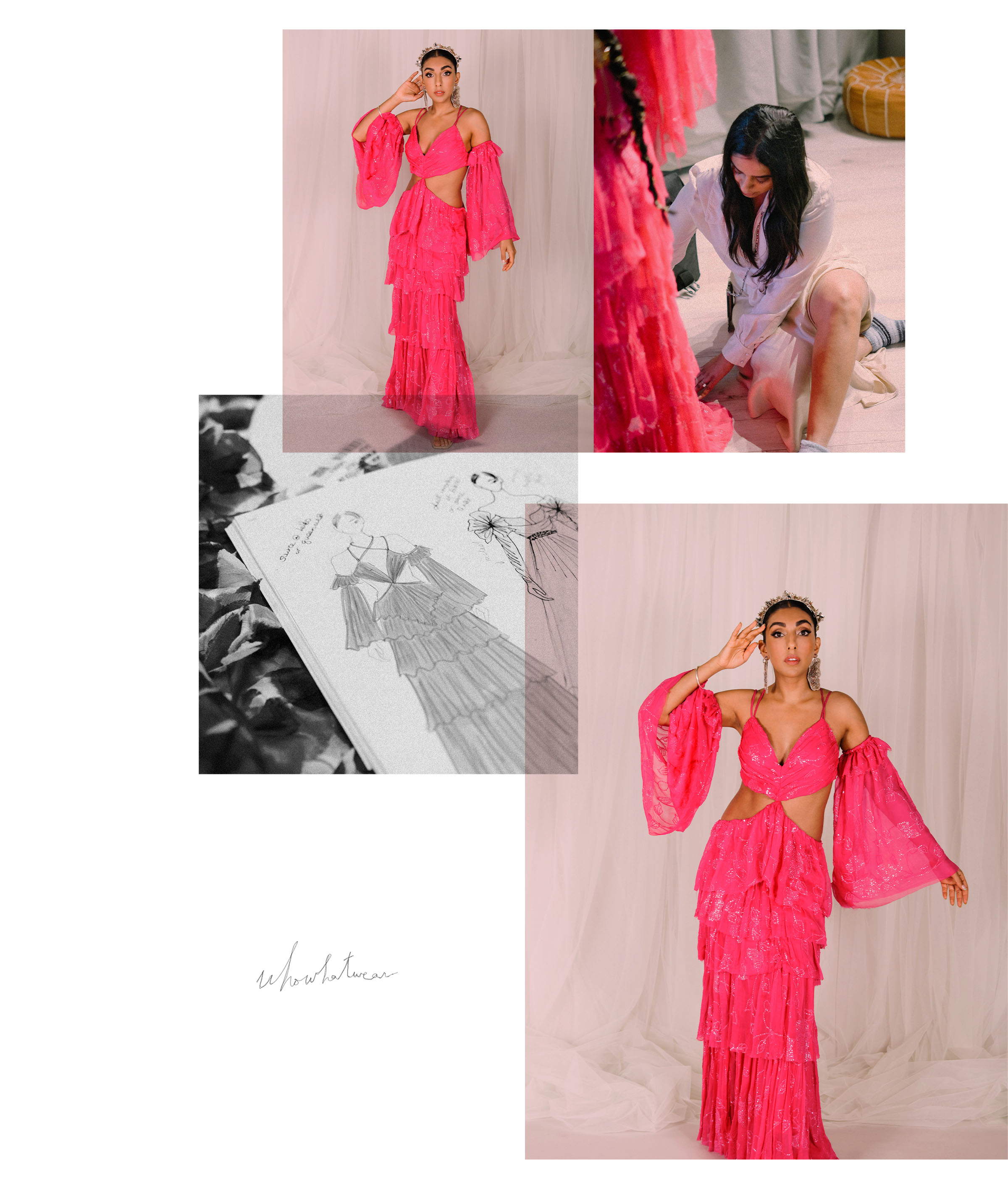

The artist has continued to explore everything from sexual trauma to depression to self-love and immigration through her writing, and she's now on her first-ever global spoken-word tour, sharing quips from her books onstage. Kaur continues to push the boundaries in poetry and fashion, so we jumped at the chance to interview the writer. Ahead, you'll hear from Kaur herself about everything from the challenges she faced in the publishing industry to what role style has played in her life to how her relationship with self-care has evolved. Plus, you'll get a sneak peek at some of the custom-made outfits she created with fashion designer Mani Jassal for her tour.

You're now on your first global spoken-word tour—tell us what inspired you to take this trip? How long will you be traveling?

I think many people might not know this about me, but I've been performing spoken-word poetry onstage for over 12 years, inspiring me to write in the first place. So I was always planning this tour; I just had to wait for things to get better with COVID-19 to get back on the road again. And I'll be traveling across the globe to perform my work for the next year and a half to two years.

Can you remember the first time you performed spoken word?

I was in high school and didn't even know what I was doing was spoken word at the time. I just saw a flyer about an open-mic night and decided to go. Looking back, I don't know what made me go to that event because it was very out of my character—I was timid, like very much a fly-on-the-wall type of person. But I wrote this terse poem. It was like four paragraphs long. It wasn't even really about anything, just teenage angst, and I performed it to a crowd of 25 people. And everyone in the audience was a decade older than I was, but they were so kind and supportive and encouraged me to keep coming back. And I fell into this incredible group of activists, community organizers, and writers. So I started performing more. I became a volunteer and a community organizer. My poetry and my politics developed together at the same time.

You have talked about everything from immigration to global warming to bodily autonomy—for you, is it important to also use your writing to speak to the larger issues happening in the world?

I don't know any other way to live. It's how I was raised. I grew up in Brampton, which is right outside of Toronto [and] has a highly immigrant working-class population. Most of our parents were refugees and immigrants as a direct result of genocides that happened in the '80s and '90s in India against the Sikh community. So the politics of it all was born and bred within us. And even within my faith, human rights are at the core of everything we do and believe. In my household, my father always said, "If you're not going to speak up, then who else will? As a free person, it's your job to fight for and make space for anyone, regardless of their appearance or who they are." So I've always felt this need to go onstage and say something. And it's been beautiful to see the world move in that direction. I hope that we only continue to do so.

Many might not know that you first started sharing your poetry online—can you tell us what compelled you to begin taking your spoken word and putting it online?

I started writing to perform, but I didn't put it on YouTube or Facebook. But my friends were like, "You write these poems, and then you perform them once at some local event, put them away, and never share them again. Maybe you should put them online." So that inspired me to start sharing them on Tumblr back in 2012, and then eventually, I came around to liking Instagram and decided to share my work there too. At the time, sharing any text graphics back in the mid-2000s on the platform wasn't common. Plus, I felt apprehensive about sharing a poem about domestic violence and alcoholism (a big issue in my community) and wondered if I should share it anonymously. But my friend again pushed me and said, "No, you need to put your name on there because you're a young brown woman, and there are not many of us doing this. We need to see you're doing this because it helps everybody become more visible." So it started as a hobby. I thought I would be like Amal Clooney and become a lawyer. But I started building a following, and eventually, my readers kept asking, "Where can I buy your books"? And that inspired me to start working on Milk and Honey.

Many might not know that your first best-selling book, Milk and Honey, was initially self-published—can you tell us a little bit about the challenges you faced navigating putting a book out into the world?

I'm such a book lover, and I grew up in public libraries but never thought that I could potentially write one. It was my community of readers that planted that seed for me. But it wasn't easy to get it out there. I had so many professors and mentors that told me nobody published poetry and there was no market for it. You can go into a bookstore now, and it's different. But back then, the poetry section was at the back of the store and filled with dead people—bless their hearts. So I initially gave up on selling the book and tried pulling poems out of it to submit to different anthologies and journals. Authors always get a lot of rejections, but I realized very quickly that there wasn't a market at the time for poems about abuse, rape, and sexual assault. Of course they would reject my work when they were publishing prose about the Canadian landscape. There are no literary anthologies for this type of work. I was trying to take apart this body of work, but it wasn't working, so I realized that if it's going to resonate, I have to deliver it in the way it's intended to be and publish it myself.

Once you had that realization, what was the process like to bring that first self-published book to life? And what was it like for it to become a New York Times best seller?

Well, I started with designing the book cover. And then I laid the entire book out on my own for over a week while listening to Beyoncé's self-titled album on repeat. I was lying on the living room carpet, and my roommates were like, "What the fuck are you doing?" But I kept at it. And once it was ready, I submitted it to the self-publishing platform. From there, it became a word-of-mouth thing and eventually started showing up on best sellers lists, and publishers began asking, "Why is this self-published poetry book showing up on these lists?" And finally, that's how I found my publisher, AMP, who I'm still with and love, but it was a wild process.

Self-publishing has this taboo around it, so how have you grappled with that as a writer?

Oh, I totally agree. There was this taboo with my first book—like, "Nobody picked you. You didn't make the cut, so is your work actually good?" It's one of the reasons I was told to not self-publish, but either way, I was going to have to deal with the stigma surrounding self-publishing or never be published. At the end of the day, who would publish a 21-year-old brown Sikh girl's poetry? Nobody. On the flip side of that, the success of having my book be a best seller was the problem of becoming too popular. Because the traditional literary community will be like, "Well, your work is not literature because you're too accessible." So I've learned a lot about that over the past eight years, and I think I've accepted that you won't please everyone.

Some of the most famous poets upheld by the literary world have largely been white men. Although, there are so many noteworthy poets of color like Maya Angelou, Sonia Sanchez, and Audre Lorde. For you, how do you hope your work continues to challenge how we define what a poet is?

In my community, everyone's a poet; everyone's allowed to share. There's no debate over whether it's better to publish the hardcover or softcover of a book first to appeal to a specific audience. Poetry happens on the ground. It's with the mothers, the fathers, and the children—it's intergenerational. Poetry, for me, has always been something that is and should be accessible to everyone. It's the language of human emotion. So I come from that world, trying to fit into a very traditional publishing world, and there's been a clash. It was this constant, "But why do I have to prove myself to you?" And I've finally gotten to a place where I don't feel I need to do that anymore. I don't need to defend myself or think I'm doing things the "wrong" way. There's no one right way to write poetry or one singular image of what a poet can be. After eight years and three books, I'm now at that point where I finally feel the most confident and powerful I've ever felt.

Speaking of feeling personally powerful, did it take time for you to get to that point as a writer? There's pressure about how you're "supposed" to write poetry, so how have you been able to detach yourself from how your work is perceived and step into your power as a writer?

I think it helped that I never wanted to be a writer. It's not something I grew up thinking I wanted to work on. I started to do it because I loved it. When I began doing spoken word, I didn't even see it as writing poetry. I called it storytelling. It was about connecting with the audience. So when I did finally begin to write poetry, it was in these abridged and condensed versions that I call peach pits. The poems you see on my Instagram or in my book are these short 10-word stanzas that are the antithesis of traditional poetry. And when I became popular, so many people were like, "This is not poetry," or they thought it was so easy to write these short poems. But what people don't know is that they start as 100 to 500 words, and like carving a peach, I remove the fuzz, the skin, and the meat around it until I can present my audience with just the peach pit. Can I make your stomach turn with just a few words? That's always been the goal for me. I've never felt the need to stray from that because it's an homage to the writing I grew up with. Long before I became an author, I grew up reading these short, condensed poems where the writers were very particular about the words they used, and no word was ever wasted. The poetry I read in high school never spoke to me, whereas my dad and I could spend hours discussing and dissecting a sentence that was only five words long. I thought that was really beautiful.

In addition to challenging what traditional poetry is, you're also very open in your work. You've written about depression, suicide, trauma, and anxiety—beyond writing, how do you take care of yourself? And how has your relationship with self-care evolved as you've grown older?

It's gotten much better. When things started going well for me, I was struggling mentally. But when you grow up with nothing (my family struggled throughout my childhood), you're always anxious. I was asking myself, "What am I going to do? I have to take care of my family." No one said I had to step up, but being the oldest of four children, you take that on. So then falling upon financial security for the first time in my life was even more stressful. It was constantly thinking, "How long will this last? Am I going to wake up, and will it all disappear? There's absolutely no way that any of this could possibly be meant for me." I was so afraid and paranoid that I doubled down on working and didn't take any time off. Eventually, I became extremely depressed and burnt-out. When I found a therapist, she was like, "Have you heard of weekends? They design those so you don't burn out." And that idea was game-changing for me. I didn't want to be lazy, and when you're depressed and at rock bottom, it feels like you're never going to get better. But as I started to do things like resting, it helped me begin to heal, and I'm so grateful for my mind and body for surviving that period. I have such an appreciation for where I am now.

In the Instagram age, it's so easy to get caught up in the performance of self-love, self-actualization, and self-care, but for you, how have you defined it and practiced it for yourself?

Self-care used to be easy and accessible, but it has felt like the wellness industry has turned self-care into a sport in the past couple of years. We're constantly feeling like we're not doing enough, falling behind, and it's getting increasingly expensive to take care of ourselves. And there is that performance element or, at least, trying to commodify and digitize the meaning of self-improvement. But I'm fortunate because, in my community, there's no meaning of life or self-improvement. We're like, "The answer is there are no answers." It's not your job to know the answers to life. It's just your job to experience it, and that's been a gift for me. My dad always jokes and asks, "What's up with people here always trying to have epiphanies?" We don't even have a word for that concept in the Sikh community. And that's been a freeing philosophy because I can get caught up in the "why," and the answer is … we're just human. We're not that important. The universe is so big, much bigger than any of our problems.

You've talked about how your identity informs how you approach every aspect of your life, from what you write to your mental health, but what about the clothing you wear?

I've always loved fashion. When we emigrated to Canada, my mom brought a bunch of clothes from India, which I wore for the early parts of my life. They were all boy clothes because we didn't have the means to buy nice things. So I remember when, in the second grade, my aunt—who worked at a Sears outlet at the time—came over to our basement apartment and gave me these red corduroy pants (they're kind of back in style now) with flowers embroidered on the hem, and she was like, "Try them on." I put them on, and I remember crying in the bathroom because it was the first time I felt like a girl, and they became my favorite piece of clothing for the next five years. And when I was in high school, my goal was to become a fashion designer, so I took classes. But I did not have the patience to do the math and pattern-making for fashion design. And while I made an entire portfolio to apply for Canada's top fashion school, the day before it was due, my dad was like, "I can't afford to send you there," so I chickened out. I ended up applying to business school, but it all worked out because a fellow Punjabi Sikh woman was studying to do the same thing in my class, and she's now who I've worked with to create all the looks for my global tour.

You partnered with a friend and fashion designer, Mani Jassal, to create all your looks for the tour—how did the idea of collaborating on your looks come about? And where did you two draw inspiration from?

So we started fabric shopping together in December and designed them together. Some of the looks she's entirely created herself, and some I've been like, "This is what I want," so it's been a collaboration every step of the way. She's so talented, and we've had so much fun working on making them together.

You spoke about how it's crucial for you to get dressed up to show up onstage fully. But what role has fashion played in just your healing journey? When dealing with self-hate, body dysmorphia, or any other form of self-harm, would you say that learning to love how you look is an essential part of the journey?

Absolutely. For me, fashion is such a powerful form of self-expression, self-care, and its own form of poetry. When you grow up, not having access to so many things and not feeling good about yourself, just living in hand-me-downs can impact your self-esteem. There's, of course, nothing wrong with secondhand clothing, and for me, it doesn't matter if I'm wearing designer or not—it's about if the clothing makes me feel unstoppable. Wearing something that you love gives you a different type of confidence. I don't think that way every day, but that's why it's so important to me to have those moments where I put something on that makes me feel powerful.

You've been in the spotlight for eight years now—how do you feel you've evolved as an artist over that time?

I finally feel like I'm free creatively. When I first signed my contract, I was legally bound to deliver two books, which felt like an enormous weight on me and made the process less fun. So when I finally released my last book, Home Body, and was no longer legally bound to anything, I swear to you [that] five book ideas came out of me. So I've learned that I'm best when I create freely. I just need to do my thing. And when I give it to my publisher, they can do what they want with it. I also think I've personally reached a point where I no longer feel the need to prove myself as not a "serious" writer or not a "one-hit wonder." I've dealt with many hardships along the way, but I've learned that I will create my best work if I value and love myself. The universe keeps delivering, and that's proven to be true thus far.

You've written three best-selling books and are now on tour. What can we expect from you next?

I accidentally wrote another book last year, so that will be coming out soon. And it's a book about the journey of self-exploration. It is not a collection of poetry, which is very exciting for me because it's a whole different territory. I'm excited for my readers to see what it is when it comes out.

What do you hope your legacy will be as an artist?

When I hear the word legacy, I get really nervous and unsure what it will be. But I hope I continue to create freely and honestly and never get distracted. I used to think that time was running out, that my best moments were already behind me. But I refuse to live life in that way anymore. I'm so excited to see the work I create later in life, and I think the best is yet to come.

You can feel that shift in your work—that you've moved through your trauma and now are focused on being present in the moment. How do you think you did that for yourself?

If you've spent so many years worried, I think at a certain point you're like, "Oh shit, why am I acting like the worry is gonna fix everything?" It's not going to do any of that, and then you just get on. For me, there's no capacity left in me to care. If I try to please one person, I disappoint another. You can't win everybody. So through writing Home Body, I started to work on my depression and realize that this moment is all we have. If I kept living my life waiting for some day in the future when I would be a better version of myself, if I kept waiting for the day to live fully, if I kept waiting to wear that sparkly dress in the back of my closet, it would never happen. That day doesn't exist at all. The only real thing is this moment; the rest is just the skin you get to before the peach pit.

Shop Kaur's poetry:

Next: Sadie Sink Is No Longer the New Kid in Town

Jasmine Fox-Suliaman is a freelance writer and editor living in New York City. What began as a pastime (blogging on Tumblr) transformed into a lifelong passion for unveiling the connection between fashion and culture on the internet and in real life. Over the last decade, she's melded her extensive edit and social background to various on-staff positions at Who What Wear, MyDomaine, and Byrdie. More recently, she’s become a freelance contributor to other publications including Vogue, Editorialist, and The Cut. Off the clock, you can find her clutching her cell phone as she's constantly scrolling through TikTok and The RealReal, in search of the next cool thing.

-

Hailey Van Lith Went Pro In Custom Coach, the Official Handbag Sponsor of the WNBA

Hailey Van Lith Went Pro In Custom Coach, the Official Handbag Sponsor of the WNBADetails inside.

By Eliza Huber

-

Chase Sui Wonders Demands Your Attention

Chase Sui Wonders Demands Your AttentionThe burgeoning actress came of age with Seth Rogen's movies. Now, she's starring in his latest project—The Studio, the Hollywood meta comedy now streaming on Apple TV+.

By Anna LaPlaca

-

Reimagining Girlhood With Zaya Wade

Reimagining Girlhood With Zaya WadeAt just 17 years old, Zaya Wade is rewriting the narrative on what it means to be a Gen Zer.

By Ana Escalante

-

What Happens When College Basketball Embraces the Tunnel 'Fit?

What Happens When College Basketball Embraces the Tunnel 'Fit?I asked Notre Dame's Maddy Westbeld and Coach Niele Ivey.

By Eliza Huber

-

Rebecca Black Is Back and Ready to Show You All of Herself This Time

Rebecca Black Is Back and Ready to Show You All of Herself This TimeThe "Friday" singer has a brand-new pop EP, Salvation.

By Jessica Baker

-

Lex Scott Davis on Joining the Suits Universe and Her Character's Iconic Wardrobe

Lex Scott Davis on Joining the Suits Universe and Her Character's Iconic WardrobeA lesson in power dressing.

By Jessica Baker

-

The Power of Styling in Sports

The Power of Styling in SportsIn conversation with Skylar Diggins-Smith and her stylist, Manny Jay.

By Eliza Huber

-

Alix Earle Takes Fashion Risks for Miu Miu (Yes, That Includes Socks With Heels)

Alix Earle Takes Fashion Risks for Miu Miu (Yes, That Includes Socks With Heels)Anything for Mrs. Prada.

By Ana Escalante