Invest In America: Meet the Political and Creative Forces Driving American Fashion's Evolution

The American fashion industry finds itself in a moment of profound uncertainty, struggling under the weight of challenges that feel as if they're pulling it in every direction. Independent designers, once the beating heart of the country's creative landscape, are now caught in a battle for survival. With financial support often flowing in favor of Europe's luxury giants, smaller, independent labels are left to navigate a marketplace where innovation is sometimes overshadowed by the loudest voices and the deepest pockets. Every season, you'll hear chatter that New York Fashion Week is dead and not worth resurrecting, with brands and buyers prioritizing shows in Milan and Paris over their home base. The Council of Fashion Designers of America, or CFDA, has made it a mission to revitalize New York—the recent appointment of Thom Browne as chairman is a large step in the right direction. "At a time when the role of designers is questioned [every day], we have to ignore the noise and focus on what matters the most to us," the designer wrote on Instagram the night before the fall 2025 shows kicked off in New York. Despite these efforts, many of this nation's great designers are flocking away in a real-time fashion brain drain.

For many emerging designers, particularly those from marginalized communities, the dream of breaking through feels increasingly distant, even as they pour every ounce of creativity and passion into their work. "Compared to other industries, fashion's adoption of DEI as an initiative came only in 2020," Sheena Butler-Young, senior correspondent at The Business of Fashion told Who What Wear. By and large, many designers we spoke with for this article only began to see both industry and customer reception to their ideas and stories in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. Retailers were on board, dedicating sacred shelf space to Black-owned businesses, and industry-led pledges like the 15 Percent Pledge began to hit the mainstream. The industry's recognition of Black talent seemed to have a ripple effect, empowering and uplifting other designers of color. But, as Butler-Young suggests, most of it was a farce. By 2022, funding seemed to dry up, leaving marginalized designers scrambling to scale back orders or rethink their production means. "Fashion's formation of diversity, equity, inclusion as a business category was a reaction. It was emotional," Butler-Young added. "And, at worst, it was performative."

At a time when the role of designers is questioned [every day], we have to ignore the noise and focus on what matters the most to us.

Here in 2025, it's created a harsh reality where economic pressures, shifting consumer behaviors, and an ever-changing political climate seem to threaten the very foundation of what American fashion once stood for—a professional outlet for society's visionary creatives. Even in this broken state, there remains an undeniable spirit—a raw, unrelenting energy that refuses to be extinguished. Independent brands, armed with little more than their vision, are still pushing boundaries, weaving together identities, cultures, and stories that have often been overlooked or silenced. To them, fashion is about much more than selling clothing—it's about crafting worlds, rewriting narratives, and challenging the expectations of what luxury and success should look like. "I do hope that American designers, just broadly, wherever they produce, do stay encouraged through the next couple of years. Sure, this administration will do things that have long-lasting effects, but we have to keep in mind that the world and life is so much bigger than these next four years," Butler-Young added. "One fact that I always like to mention is that per the U.S. census, by 2045, this country will be majority non-white. … That's who you're going to have to speak to [as a designer] in the next 20 years."

Despite the daunting odds, there's a sense of determination, a quiet optimism that pulses through this fractured industry. In the face of economic instability, shifting trends, and the weight of an unforgiving market, these designers are finding ways to hold their ground. They are drawing on their roots, their communities, and their ingenuity to keep going. It's a testament to their resilience—an affirmation that even in the most challenging times, creativity still has the power to thrive and perhaps, just perhaps, redefine the future of American fashion.

Jacques Agbobly was born and raised in Lomé, Togo, surrounded by local seamstresses and tailors who cut, sewed, and fit garments in extra rooms rented out by Agbobly's grandmother. After moving to the United States and attending Parsons School of Design, Agbobly established their knitwear brand in an effort to bridge the gap between their Lomé roots and newfound career in New York. "Having grown up between cultures, I use fashion to craft a universe that feels both nostalgic and forward-thinking, where African craftsmanship meets contemporary design," the designer tells Who What Wear. "Agbobly isn't just about garments; it's about storytelling, identity, and redefining what luxury means for a global, diasporic community." Their whimsical, colorful designs are pulled from personal and collective memories—childhood games, vibrant textures, and sacred moments of joy that don't make it into the mainstream when representing Black life.

I want to create a world where Blackness isn't confined to narratives of resilience but is also seen through the lens of whimsy, nostalgia, and innovation.

In 2024, Agbobly became a semifinalist for the prestigious LVMH Prize, aimed at supporting and uplifting independent and emerging labels. Despite the assumption that a large corporate stamp of approval would be a permanent solution for young brands to gain recognition and financial support, Agbobly admits they still struggle with the weight of the industry. Of course, larger brands with financial support will always be there, but the key in remaining focused and resilient, according to Agbobly, is by leaning into the brand's community of loyal supporters, buyers, and craftspeople who are working together on the brand's larger-than-life storytelling. Each woven piece, stitch, or crochet adds to the Agbobly world, centering joy and Afropolitans. "There's often an expectation that Black designers must center our work on race or struggle. While those themes inevitably shape my perspective, Agbobly exists beyond them," they add. "I want to create a world where Blackness isn't confined to narratives of resilience but is also seen through the lens of whimsy, nostalgia, and innovation."

Despite the financial struggles, like most other designers, Agbobly remains hopeful. Sure, brands are coming and going (most notably uprooting to the European capitals, as several labels have recently done), but there's still undeniable grit and spirit behind the independent labels in New York. "We just need to keep pushing forward, and with the right support and resources, I believe the future of American fashion is bright," Agbobly added. "We have to keep going, especially in these tough times."

Sergio Hudson derives all of his collections from joy and Black excellence. The designer, who officially started showing on the New York Fashion Week calendar in 2020, was raised in the South, where prim-and-proper American couture was the foundation for his tight-knit Black community. What once was joy, though, has turned into a more realistic gaze at the state of the industry. Although Hudson is an established veteran on the scene (he began his label in 2014), the American sportswear designer only had one word to say about the state of affairs of the fashion business in this country: "Scary. That's the first thing that comes to mind to me," Hudson admits. "We have our supporters and people who do really see us, but when you look at the marketplace, as an American designer, that category is marginalized compared to the luxury houses of Europe. And then, when you are from a marginalized group or come from an ethnic background, it marginalizes you even more."

For years, American fashion designers have been compared to those at the helm of Europe's conglomerate-backed luxury maisons. The truth is, though, you can't really compare it—America feels like the Wild West of the fashion industry, with innovation, grit, and craftiness coming above all else as a lagging retail industry feels like it's creeping to a halt. (Hudson nods to the controversial news that came from American retailer Saks the other day, with the brand announcing that it was extending the amount of time it took to pay vendors—some of which are independently backed labels that are already struggling to survive.) "As time goes on, the goalposts to success just get farther and farther away." Despite the monetary challenges that come from being an independently owned American brand, Hudson is still doubling down on his commitment to support United States garment workers. Naturally, it comes at a higher burden to bear, financially. "Maybe that's why some designers don't stay in business, but I just can't allow my integrity to be overtaken by being money hungry," he says. "I'm a young Black man from South Carolina. I was always taught you have to be better. You have to do more to be considered as equal. So that's how I operate in life and everything that I do."

Support an independent brand, and you'll continue to see this industry grow.

During our conversation, Hudson is honest about the pursuit of the business and his dreams: He's tired of being put into a box as a Black designer, with the industry at large often thinking Black designers' aesthetics must align with a certain vision, whether it be streetwear or clothes pulling from traditional African motifs and prints. "I feel like when people look at me as a human being, they see a Black man first; they don't see an American sportswear designer. And that's the problem," Hudson adds. "People put me in a box by saying I can't be just an American sportswear designer that makes a great trench coat or a suit that a woman would want to wear. There's no space in that, because that's how [the industry] views Black designers."

It's not all bleak, though. There's a beauty in surviving, Hudson says. It's hard not to acknowledge that we're in a dark time in history, given the state of the economy and politics, but Hudson says he plans on making it through by any means necessary. "The art form of making beautiful clothing for women to wear has kind of been lost, and I feel like the support needs to come back for that," Hudson says. "So support an independent brand, and you'll continue to see this industry grow. When we stop supporting independent brands, that's when, to me, the industry dies."

You might recognize Jackson Wiederhoeft's whimsical, otherworldly designs before you recognize the designer themself. Tucked away in the heart of the Garment District in New York is where the Wiederhoeft world takes flight in a fantastical saloon covered in boned corsets and gowns dripping in jewels. Although Wiederhoeft has long been in the industry (the designer famously worked for CFDA Chairman Thom Browne), it wasn't until 2019 when the label came to life. "There wasn't a business plan out the gate; it was more of a creative project," Wiederhoeft explained. "But after that first collection, I saw a way that it could actually work out."

First and foremost, Wiederhoeft is a queer brand. In terms of the storytelling, vision, and collaborators, the designer explains every choice is thoughtfully and intentionally strange and out of place, nodding to the true definition of queer in a literal sense. "We are people who really celebrate things that seem to be misplaced or precariously placed," Wiederhoeft explained. "Everything is beautiful and lovely, but there's always a sense of danger that is inherently tied to everything." It's worth noting that the brand's surge in popularity within the bridal space also comes at a delicate time given that the current presidential administration has signed a series of anti-trans executive orders into law. (When asked if the designer has struggled with coming to terms with the anti-LGBTQIA+ rhetoric that's surging in the country, Wiederhoeft responds cooly. They're fighting the good fight for as long as it takes, whether or not rights get taken away. "It's disheartening, but I think revenge [by simply existing] is sweet, so there's that, too," they say.)

One of the most important things I can do is also supporting American manufacturing and New York City manufacturing.

Just last year, Wiederhoeft was a finalist for the prestigious CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund award that aims to highlight emerging American designers with a unique point of view. At this point, the brand doesn't need the press when it comes to doubling down on what makes American fashion so great. (Lady Gaga, Sabrina Carpenter, and Ice Spice are all friends of the house.) But when asked what the future of American fashion looks like, especially given the fact that the brand produces everything in the Garment District, Wiederhoeft practically lights up. "Being an American designer, I think one of the most important things I can do is also supporting American manufacturing and New York City manufacturing. Almost every business I work with in New York is immigrant-owned, woman-owned, which is so New York and so badass," Wierderhoeft says. "I think supporting that is such a privilege that I get to engage in, and I really want to do that forever."

Allina Liu attributes her drive and love of design to the chip on her shoulder she had as a kid. The 33-year-old New York–based designer jokes that her Chinese immigrant parents might be partly to blame for her rebellious phase. After stints at The Row, J.Crew, and Rebecca Taylor, she decided to start her own label based on exploring the female form and the BDSM community. Enter the self-titled label that's become a fashion darling among New York City's young scene. Flowy dresses tied together with bows and voluminous skirts aren't just pretty means to an end—for Liu, the brand is about tapping into the strange. (The brand's last presentation during New York Fashion Week featured creepy smiles, doll-like silhouettes, and innocent-seeming models all in reference to religious cults.)

After a couple years in business, though, Liu quietly shut down due to financial constraints. It wasn't until she pivoted into the tech sector that she had the funds to relaunch years later in 2020. It's a stark reminder that, for most designers of color in the United States, there are no inventors or conglomerate funding to help small designers stay afloat. That's why Liu produces in Guangzhou, China, known as one of the largest manufacturing hubs on the planet. Without exporting the majority of her business overseas, there's no way she would be able to sustain her brand. Given most Americans' reliance on fast fashion and hyper-fast retailers like Amazon, there's a sticky association between the perception of Liu's production and unethical, subpar garment factories.

Right now, it's difficult, and it's complicated to identify as an American designer.

"I'm ethnically Chinese, and I take a lot of pride in the term Made in China. Do people see my last name and just assume I'm producing garbage made by 2-year-olds for pennies?" Liu asks out loud. "I've been to my factory—I know the people, and I've seen the conditions. Ethics are massive for me. China is so much more than just sweatshops. I think it's really, really wildly racist to lump an entire country of people together for a couple people's mistakes."

What does being an American designer mean to her? It's heavily tied to being an American in general. "It's tough," Liu admits. The looming threat of a catastrophic trade war alongside reverberating impacts of anti-Asian rhetoric would lead most people to err on the side of pessimism. But, above all, being an American designer means being nimble and working with what you've got, despite it all. "Right now, it's difficult, and it's complicated to identify as an American designer. I think that we have been put in a position where our administration doesn't reflect our personal beliefs. All I can do is use whatever small platform I have to really embrace my community that believes in me and that I believe in them right back."

Mónica Santos Gil was tired of seeing everyone in New York wear black, so naturally, she started her own label. While the intentions behind the brand might have been rooted in a slight joke, the designer's love for color isn't—her brand, Santos by Mónica, established during the pandemic in Puerto Rico, is inspired by the rich, vibrant colors of the Caribbean island she grew up on. After stints in California and New York, the ready-to-wear and handbag designer began to focus on sustainability and biomaterials, another nod to her roots. "As an independent designer, I think a lot about representation—and not just in terms of who wears my pieces but also how they're made and what stories they tell, down to the materials I'm using." Santos Gil explains.

Being in the American fashion industry right now means being solution-driven, regardless of what's going on politically or economically.

As the daughter of two creatives who prioritized their lush, tropical home, Santos Gil knew she had to be intentional about the structure of her business when she first started. As an American founder, like many other young designers, there are limited funds available to make your dreams a reality. Santos Gil prioritized high-quality biomaterials like cactus leather in lieu of massive first-run batches, opting to sew and cut everything herself for the first few launches. Although she now has two factories working on the label—one in the United States and another in Mexico—at her core, Santos Gil believes being an independent brand is about being resourceful and nimble. "Being in the American fashion industry right now means being solution-driven, regardless of what's going on politically or economically," she added. "It's at the cornerstone of what an emerging or young brand is, especially if you don't have the capital or a factory or financial backing."

Contrary to popular belief, it is possible to create and execute a brand right now, even if the marketplace is so tough, she adds. You might pull out your hair in the process, but it's all worth it. "It's all the more rewarding when everything falls into place," Gil Santos finishes. It's a reminder that even in challenging times, creativity, perseverance, and resourcefulness can make your vision a reality—something she's living proof of with every collection she brings to life.

Yitao Li lives between two worlds. The 26-year-old has spent half of her life in China, only moving to the United States at 13 years old. Her label, Taottao, was born out of a passion project for geometric design and patternmaking. (She was on the math team during high school, she jokes.) While Li might not see herself as a fully born-and-bred American designer, her brand is quintessentially American, relying on New York aesthetics and edge, born out of her schooling from the Fashion Institute of Technology. Like most young designers whose customer base lives in the United States, Li is playing on the narrative of what the modern girl wants to wear—not the modern woman. There are micro miniskirts layered atop leggings, sherpa-lined neck pillow–style scarves, and baggy pants that are definitely Dimes Square approved. Although the brand is only three years old, Li has already garnered a sizable following both in New York and abroad.

"While America strongly supports originality and independent designers, that often comes with high costs, making it difficult for everyone to support emerging talent," Li admits. While her small team produces between Shenzhen and Jersey City, the bulk of the brand's manufacturing happens in China while the marketing occurs in the United States. "Coming from a hardworking country like China, where I have close access to skilled artisans and technicians, has allowed me to bridge that gap, making original design more accessible."

Being an American designer means being a fusion designer—blending cultures and bringing out the best of both worlds.

In the midst of economic tariffs imposed by the United States, it's hard not to spiral. Li admits that, although exporting and importing garments might become more expensive and challenging, there's still an advantage as a small, independent designer producing overseas—it's still a net positive as it pertains to profits and being on-site to see production firsthand. Regardless, there are certain privileges that come from being an America-based designer. "Building a brand comes with different challenges in both the U.S. and China," Li says. "The U.S. offers more creative freedom, while China’s efficiency and technical expertise in production are invaluable. While copyright remains a challenge in China, working closely with skilled artisans there is crucial to my design process."

Despite the challenges, Li sees the experience as a valuable learning curve that has only strengthened her determination to push her brand forward. The contrast between the two worlds she navigates—China's competitive fashion landscape and the creative freedom she enjoys in the United States—has given Li a unique perspective on the industry as a global-first designer.

Ana Escalante is an award-winning journalist and Gen Z editor known for her sharp takes on fashion and culture. She’s covered everything from Copenhagen Fashion Week to Roe v. Wade protests as the Editorial Assistant at Glamour after earning her journalism degree at the University of Florida in 2021. At Who What Wear, Ana mixes wit with unapologetic commentary in long-form fashion and beauty content, creating pieces that resonate with a digital-first generation. If it’s smart, snarky, and unexpected, chances are her name’s on it.

-

What Happens When College Basketball Embraces the Tunnel 'Fit?

What Happens When College Basketball Embraces the Tunnel 'Fit?I asked Notre Dame's Maddy Westbeld and Coach Niele Ivey.

By Eliza Huber

-

Is It Just Me, or Is Every Fashion Person Wearing This New York City Jewelry Brand?

Is It Just Me, or Is Every Fashion Person Wearing This New York City Jewelry Brand?Now, I understand why.

By Nikki Chwatt

-

35 Incredibly Chic Luxury Finds I Would Immediately Buy If My Salary Tripled Tomorrow

35 Incredibly Chic Luxury Finds I Would Immediately Buy If My Salary Tripled TomorrowA girl can dream, right?

By Jennifer Camp Forbes

-

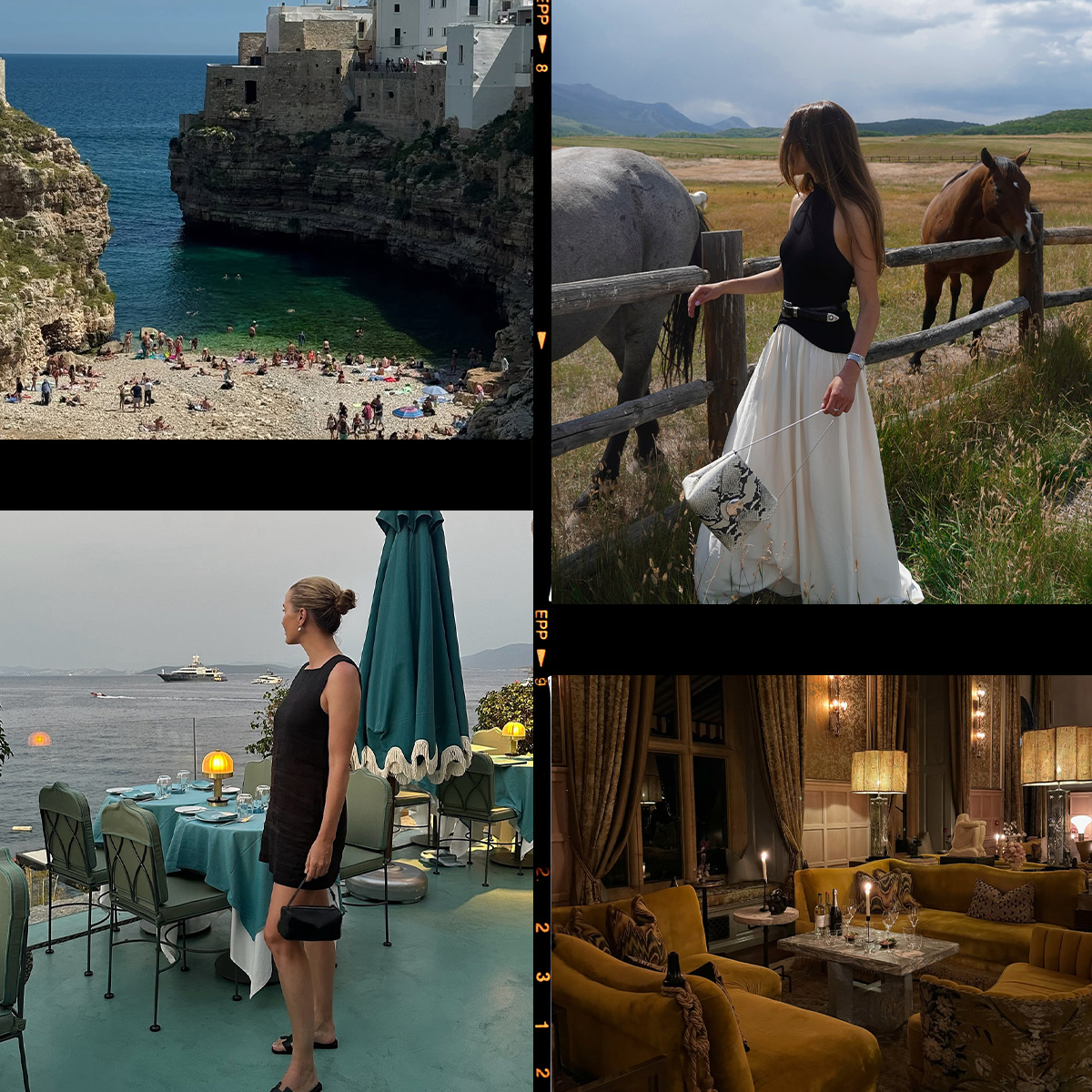

5 Europe-Based Influencers I Follow to Find Out What the New Designer It Items Are

5 Europe-Based Influencers I Follow to Find Out What the New Designer It Items AreReady for some wardrobe envy?

By Allyson Payer

-

The Power of Styling in Sports

The Power of Styling in SportsIn conversation with Skylar Diggins-Smith and her stylist, Manny Jay.

By Eliza Huber

-

Alix Earle Takes Fashion Risks for Miu Miu (Yes, That Includes Socks With Heels)

Alix Earle Takes Fashion Risks for Miu Miu (Yes, That Includes Socks With Heels)Anything for Mrs. Prada.

By Ana Escalante

-

Julian Klausner's Dries Van Noten Is Everything We Collectively Hoped It Would Be (and Then Some)

Julian Klausner's Dries Van Noten Is Everything We Collectively Hoped It Would Be (and Then Some)A stunning debut.

By Eliza Huber

-

Meet Lexie Hull, TikTok's Favorite Shooting Guard Turned Influencer

Meet Lexie Hull, TikTok's Favorite Shooting Guard Turned InfluencerI spoke with Athleta's newest Power of She Collective member.

By Eliza Huber